Decoding the Discussion: In the Senate AI Hearing, Uncertainty Speaks Louder than Consensus

May's committee hearing showed a remarkable bipartisan consensus on the need to regulate AI. Yet the road ahead presents complex challenges that could disrupt this unified momentum.

We have come a long way from the days when senators described the internet as a “series of tubes”. At last month’s Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on AI, Senator Richard Blumenthal kicked off the opening statements with a deepfake of his voice and a statement written by ChatGPT, and senators spent three hours talking with top AI leaders about issues of transparency, privacy, and more.

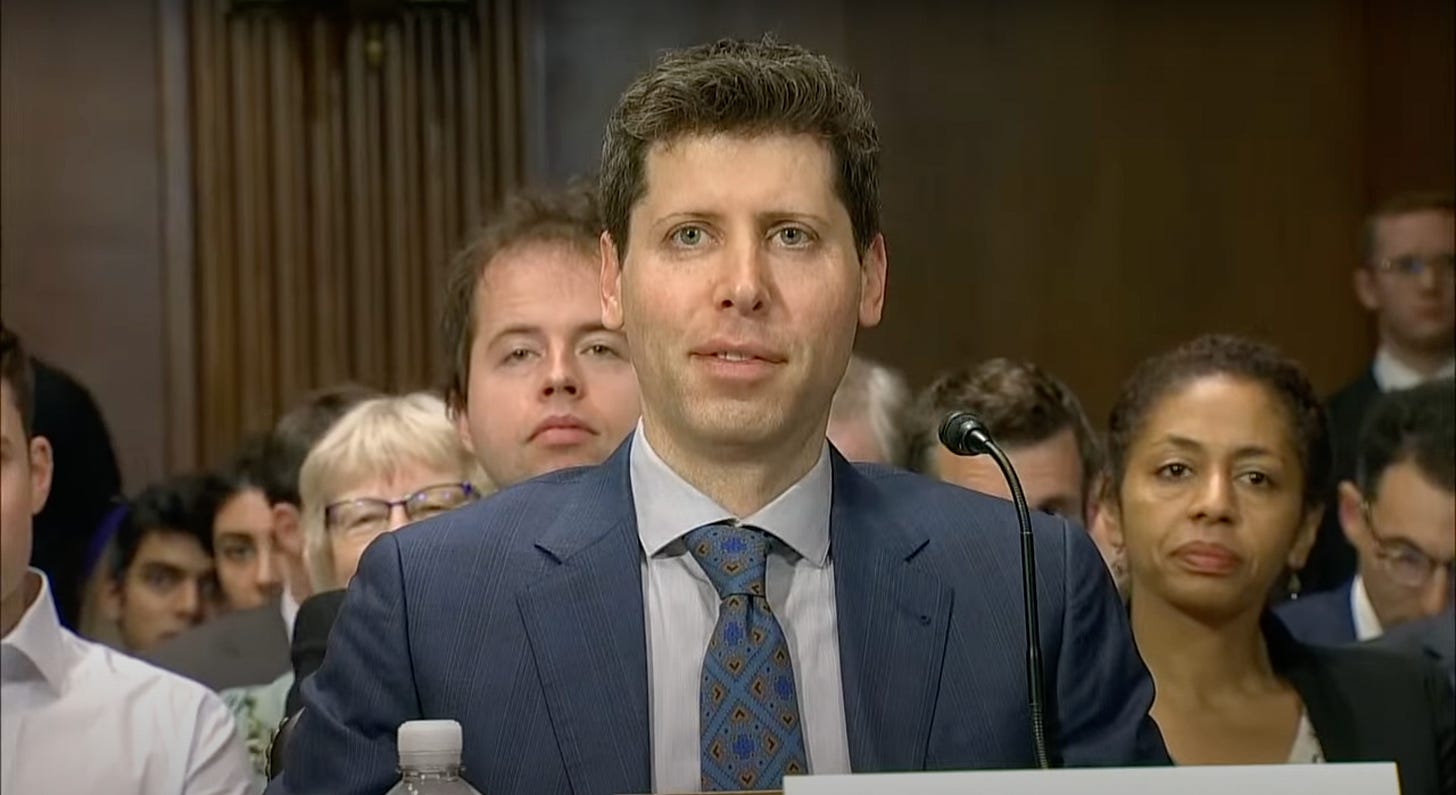

The past half-year of AI frenzy seems to have resulted in a genuine desire for lawmakers to come together with industry to understand this new technology and develop standards to promote its safe development. Some, in fact, were quick to point out that the interaction seemed almost too friendly. The three key witnesses — OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, IBM Chief Privacy & Trust Officer Christina Montgomery, and New York University Professor Gary Marcus — faced a much warmer environment compared to the more antagonistic congressional hearings of past tech executives like Mark Zuckerberg. While it’s possible that this unprecedented friendliness signals better cooperation between government and industry, many analysts warn that it indicates a high likelihood of regulatory capture.

Yet if there’s one thing known to be true in American politics, it’s that the path from a policy discussion to a newly adopted bill is a long one. With top tech companies pouring nearly $70 million into congressional lobbying last year, and the vast majority of bills never making it past committee, the latest hearings are only the beginning of the long road to come.

To see where AI regulation may be headed, it’s helpful to look into the subtle aspects of this hearing and see what questions are still left unanswered. Finding points of agreement is valuable, but it’s in the areas of uncertainty where we have the greatest opportunity to actively shape the discourse — ensuring that it’s well-informed, productive, and focused on the issues that matter to all of us.

Here’s what still remains to be debated:

1. Which concerns will be lawmakers’ primary focus?

While developing standards for the responsible use of technology appears to be a common goal, the scope of proposed regulations will vary significantly depending on which problems they aim to target. The seven-minute questioning rounds converged towards many common themes, showing hope for future government action on fronts like misinformation and system transparency.